Month: October 2015

Thomas Jefferson’s Qu’ran: Islam And Religious Freedom

The inscription on Thomas Jefferson’s tombstone, as he stipulated, reads Here was buried Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of american Independence, of the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom, and father of the University of Virginia.

Thomas Jefferson (April 13 April 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Father, the principal author of the Declaration of Independence (1776), and the third President of the United States (1801–1809). He was an ardent proponent of democracy and embraced the principles of republicanism and the rights of the individual.

A champion of the Age of Enlightenment, Jefferson was a polymath in the arts, sciences, and politics. He was a proven architect in the classical tradition, and designed his home Monticello, near Charlottesville, Virginia, Virginia’s state capitol and other important buildings. He was keenly interested in science, invention, architecture, religion, and philosophy, and served as president of the American Philosophical Society. Besides English, he was well versed in Latin and Greek, proficient in French, Italian, and Spanish, and studied other languages and linguistic. He founded the University of Virginia after his presidency. Although not a strong orator, Jefferson was a skilled writer and corresponded with many influential people in America and Europe.

Jefferson’s religious and spiritual beliefs were a combination of various religious and theological precepts. Around 1764, Jefferson had lost faith in “orthodox” Christianity after he had tested the New Testament for the consistency of its teachings, and found it to be severely lacking. Jefferson later wrote that he found two strains within the Bible, one that was as “diamonds” of the “purest moral teaching”,and one that was as a “dunghill” of “priest-craft and roguery”. After leaving “Christian orthodoxy” behind, he continued to refer to himself as a “Christian,” though no longer as an “orthodox Christian”.

Jefferson praised the morality of Jesus and edited a compilation of his teachings, omitting the miracles and supernatural elements of the biblical account, titling it The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth.This book is now most popularly known as the Jefferson Bible. He claimed that Christianity possessed, “the most sublime and benevolent code of morals which has ever been offered to man.” Jefferson was firmly anticlerical saying that in “every country and every age, the priest has been hostile to liberty … they have perverted the purest religion ever preached to man into mystery and jargon, unintelligible to all mankind, and therefore the safer for their purposes.”

Jefferson’s form of Christianity included a stern code of personal moral conduct and also drew inspiration from classical literature. While his new belief system retained some Christian principles it rejected many of the orthodox tenets of Christianity of his day and was especially hostile to the Catholic Church as he saw it operate in France. Jefferson advanced the idea of Separation of Church and State, believing that the government should not have an official religion while at the same time it should not prohibit any particular religious expression. He first expressed these thoughts in an 1802 letter to the Danbury Baptists in Connecticut.

Throughout his life Jefferson was intensely interested in theology, biblical study, and morality. As a landowner he played a role in governing his local Episcopal Church; in terms of belief he subscribed to the moral philosophy of Jesus, but he did not subscribe to much of what he described as the “dung” of popular Christian theology. When he was home he attended the Episcopal church and raised his daughters in that faith. Over time, some have described Jefferson as a Deist; however, due to his belief in a God which is actively involved in the guidance of human history, the modern understanding of the word “Deism” may not entirely describe Jefferson’s system of beliefs.

In a private letter to Benjamin Rush in 1803 Jefferson explained some aspects of his own personal belief system regarding Christianity: “To the corruptions of Christianity I am, indeed, opposed; but not to the genuine precepts of Jesus himself. I am a Christian, in the only sense in which he wished any one to be; sincerely attached to his doctrines, in preference to all others; ascribing to himself every human excellence…” Jefferson noted both benevolence and contradictions in Christian doctrine.

The Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom was drafted in 1777 (however it was not first introduced into the Virginia General Assembly until 1779) by Thomas Jefferson in the city of Fredericksburg, Virginia. On January 16, 1786, the Assembly enacted the statute into the state’s law. The statute disestablished the Church of England in Virginia and guaranteed freedom of religion to people of all religious faiths, including Catholics, Jews, Muslims as well as members of all Protestant denominations.

The statute was a notable precursor of the Establishment Clause and Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution.

The Statute for Religious Freedom is one of only three accomplishments Jefferson instructed be put in his epitaph.

Text of the Statute:

“An Act for establishing religious Freedom.

Whereas, Almighty God hath created the mind free;

That all attempts to influence it by temporal punishments or burdens, or by civil incapacities tend only to beget habits of hypocrisy and meanness, and therefore are a departure from the plan of the holy author of our religion, who being Lord, both of body and mind yet chose not to propagate it by coercion on either, as was in his Almighty power to do,

That the impious presumption of legislators and rulers, civil as well as ecclesiastical, who, being themselves but fallible and uninspired men have assumed dominion over the faith of others, setting up their own opinions and modes of thinking as the only true and infallible, and as such endeavoring to impose them on others, hath established and maintained false religions over the greatest part of the world and through all time;

That to compel a man to furnish contributions of money for the propagation of opinions, which he disbelieves is sinful and tyrannical;

That even the forcing him to support this or that teacher of his own religious persuasion is depriving him of the comfortable liberty of giving his contributions to the particular pastor, whose morals he would make his pattern, and whose powers he feels most persuasive to righteousness, and is withdrawing from the Ministry those temporary rewards, which, proceeding from an approbation of their personal conduct are an additional incitement to earnest and unremitting labours for the instruction of mankind;

That our civil rights have no dependence on our religious opinions any more than our opinions in physics or geometry,

That therefore the proscribing any citizen as unworthy the public confidence, by laying upon him an incapacity of being called to offices of trust and emolument, unless he profess or renounce this or that religious opinion, is depriving him injurious of those privileges and advantages, to which, in common with his fellow citizens, he has a natural right,

That it tends only to corrupt the principles of that very Religion it is meant to encourage, by bribing with a monopoly of worldly honors and emoluments those who will externally profess and conform to it;

That though indeed, these are criminal who do not withstand such temptation, yet neither are those innocent who lay the bait in their way;

That to suffer the civil magistrate to intrude his powers into the field of opinion and to restrain the profession or propagation of principles on supposition of their ill tendency is a dangerous fallacy which at once destroys all religious liberty because he being of course judge of that tendency will make his opinions the rule of judgment and approve or condemn the sentiments of others only as they shall square with or differ from his own;

That it is time enough for the rightful purposes of civil government, for its officers to interfere when principles break out into overt acts against peace and good order;

And finally, that Truth is great, and will prevail if left to herself, that she is the proper and sufficient antagonist to error, and has nothing to fear from the conflict, unless by human interposition disarmed of her natural weapons free argument and debate, errors ceasing to be dangerous when it is permitted freely to contradict them:

Be it enacted by General Assembly that no man shall be compelled to frequent or support any religious worship, place, or ministry whatsoever, nor shall be enforced, restrained, molested, or burdened in his body or goods, nor shall otherwise suffer on account of his religious opinions or belief, but that all men shall be free to profess, and by argument to maintain, their opinions in matters of Religion, and that the same shall in no wise diminish, enlarge or affect their civil capacities. And though we well know that this Assembly elected by the people for the ordinary purposes of Legislation only, have no power to restrain the acts of succeeding Assemblies constituted with powers equal to our own, and that therefore to declare this act irrevocable would be of no effect in law; yet we are free to declare, and do declare that the rights hereby asserted, are of the natural rights of mankind, and that if any act shall be hereafter passed to repeal the present or to narrow its operation, such act will be an infringement of natural right.”

Sura Al-Baqara, Ayat 256 (There Is No Compulsion In Religion)

Verse (ayah) 256 of Al-Baqara is a widely quoted verse in the Islamic scripture, the Qur’an. The verse includes the phrase that “there is no compulsion in religion.”

The version is important to the debate on conversion to Islam and apostasy from Islam, specifically whether the “compulsion” is taken to refer to conversion to or apostasy from Islam. The overwhelming majority of Muslim scholars consider that verse to be a Medinan one, when Muslims lived in their period of political ascendance, and to be non abrogated, including Ibn Qayyim, Ibn Kathir, Al-Tabari, Abi ‘Ubayd, Al-Jassas, Makki bin Abi Talib, Al-Nahhas, Al-Suyuti. According to all the theories of language elaborated by Muslim legal scholars, the Qur’anic proclamation that ‘There is no compulsion in religion. The right path has been distinguished from error’ is as absolute and universal a statement as one finds, and so under no condition should an individual be forced to accept a religion or belief against his or her will according to the Qur’an.

Ibn Kathir’s interpretation

The Qur’an commentator (Muffasir) Ibn Kathir, a Sunni, suggests that the verse implies that Muslims should not force anyone to convert to Islam since the truth of Islam is so self-evident that no one is in need of being coerced into it,

There is no compulsion in religion. Verily, the right path has become distinct from the wrong path. لاَ إِكْرَاهَ فِي الدِّينِ (There is no compulsion in religion), meaning, “Do not force anyone to become Muslim, for Islam is plain and clear, and its proofs and evidence are plain and clear. Therefore, there is no need to force anyone to embrace Islam. Rather, whoever Allah directs to Islam, opens his heart for it and enlightens his mind, will embrace Islam with certainty. Whoever Allah blinds his heart and seals his hearing and sight, then he will not benefit from being forced to embrace Islam. It was reported that; the Ansar were the reason behind revealing this Ayah, although its indication is general in meaning. Ibn Jarir recorded that Ibn Abbas said (that before Islam), “When (an Ansar) woman would not bear children who would live, she would vow that if she gives birth to a child who remains alive, she would raise him as a Jew. When Banu An-Nadir (the Jewish tribe) were evacuated (from Al-Madinah), some of the children of the Ansar were being raised among them, and the Ansar said, `We will not abandon our children.’ Allah revealed, لاَ إِكْرَاهَ فِي الدِّينِ قَد تَّبَيَّنَ الرُّشْدُ مِنَ الْغَيِّ (There is no compulsion in religion. Verily, the right path has become distinct from the wrong path). Abu Dawud and An-Nasa’i also recorded this Hadith. As for the Hadith that Imam Ahmad recorded, in which Anas said that the Messenger of Allah said to a man, أَسْلِم “Embrace Islam. The man said, “I dislike it. The Prophet said, وَإِنْ كُنْتَ كَارِهًا “Even if you dislike it. First, this is an authentic Hadith, with only three narrators between Imam Ahmad and the Prophet. However, it is not relevant to the subject under discussion, for the Prophet did not force that man to become Muslim. The Prophet merely invited this man to become Muslim, and he replied that he does not find himself eager to become Muslim. The Prophet said to the man that even though he dislikes embracing Islam, he should still embrace it, `for Allah will grant you sincerity and true intent.’

Jefferson’s political ideals were greatly influenced by some of the greatest thinkers of the Age of Enlightenment; John Lock (1632-1704), Francis Bacon (1562-1626), and Isaac Newton (1642-1727), whom he considered the three greatest men that ever lived.

The Age of Enlightenment or simply the Enlightenment or Age of Reason is an era from the 1620’s to the 1780’s in which cultural and intellectual forces in Western Europe emphasized reason, analysis, and individualism rather than traditional lines of authority. It was promoted by philosophies and local thinkers in urban coffee houses, salons, and Masonic lodges. It challenged the authority of institutions that were deeply rooted in society, especially the Roman Catholic church; there was much talk of ways to reform society with toleration, science and skepticism.

Jefferson was also influenced by the writings of Gibbon, hume, Robertson, Bolingbroke, Montesquieu, and Voltaire. But it was the writings of Voltaire that created an adverse opinion of Muhammad in Europe and by extension America.

It may not have been a coincident that the 3 million people strong anti-Islam, anti-terrorism protest in Paris was held on Boulevard Voltaire, named in honor of the French playwright and philosopher Voltaire. Some of the participants interviewed by BBC said Voltaire had a deep significance to them both in relation to the subject and to history. Voltaire found prophet Mohammed grotesque in character and conduct.

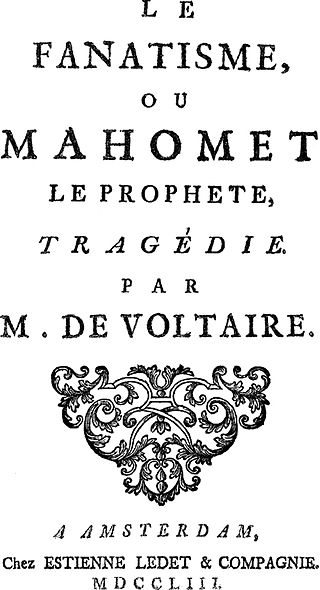

Mahomet (Play)

Mahomet (French: Le fanatisme, ou Mahomet le Prophète, literally Fanaticism, or Mahomet the Prophet) is a five-act tragedy written in 1736 by French playwright and philosopher Voltaire. It received its debut performance in Lille on 25 April 1741.

The play is a study of religious fanaticism and self-serving manipulation based on an episode in the traditional biography of Muhammad in which he orders the murder of his critics. Voltaire described the play as “written in opposition to the founder of a false and barbarous sect”.

The story of “Mahomet” unfolds during Muhammad’s post exile siege of Mecca in 630 AD, when the opposing forces are under a short term truce called to discuss the therms and course of the war.

In the first act the audience is introduced to a fictional leader of the Meccans, Zopir, an ardent and defiant advocate of free will and liberty who rejects Mahomet. Mahomet is presented through his conversations with his second in command Omar and with his opponent Zopir and with two of Zopir’s long lost children (Seid and Palmira) whom, unbeknownst to Zopir, Mahomet had abducted and enslaved in their infancy, fifteen years earlier.

The now young and beautiful captive Palmira has become the object of Mahomet’s desires and jealousy. Having observed a growing affection between Palmira and Seid, Mahomet devises a plan to steer Seid away from her heart by indoctrinating young Seid in religious fanaticism and sending him on a suicide attack to assassinate Zopir in Mecca, an event which he hopes will rid him of both Zopir and Seid and free Palmira’s affections for his own conquest. Mahomet invokes divine authority to justify his conduct.

Seid, still respectful of Zopir’s nobility of character, hesitates at first about carrying out his assignment, but eventually his fanatical loyalty to Mahomet overtakes him[4] and he slays Zopir. Phanor arrives and reveals to Seid and Palmira to their disbelief that Zopir was their father. Omar arrives and deceptively orders Seid arrested for Zopir’s murder despite knowing that it was Mahomet who had ordered the assassination. Mahomet decides to cover up the whole event so as to not be seen as the deceitful impostor and tyrant that he is.

Having now uncovered Mahomet’s “vile” deception Palmira renounces Mahomet’s god and commits suicide rather than to fall into the clutches of Mahomet.

Analysis and Reception

The play is a direct assault on the moral character of Muhammad. Omar is a known historical figure who became second caliph; the characters of Seid and Palmira represent Muhammad’s adopted son Zayd ibn Harithah and his wife Zaynab bint Jahsh. The play’s plot contradicts the version of the respective Surah in the Qur’an.

Pierre Milza, posits that, it may have been “the intolerance of the Catholic Church and its crimes done on behalf of the Christ” that were targeted by the philosopher, Voltaire’s own statement about it in a letter in 1742 was quite vague: “I tried to show in it into what horrible excesses fanaticism, led by an impostor, can plunge weak minds.”

It is only in another letter dated from the same year that he explains that this plot is an implicit reference to Jacques Clement, the monk who assassinated Henri III in 1589.

However, it was considered that Islam wasn’t the only focus of the plot and that his aim when writing the text was to condemn “the intolerance of the Church and the crimes that have been committed in the name of the Christ”.

Napoleon during his captivity on St Helena criticized Voltaire’s Mahomet, and said Voltaire had made him merely an impostor and a tyrant, without representing him as a “great man”:

- “Mahomet was the subject of deep criticism. ‘Voltaire,’ said the Emperor, ‘in the character and conduct of his hero, has departed both from nature and history. He has degraded Mahomet, by making him descend to the lowest intrigues. He has represented a great man, who changed the face of the world, acting like a scoundrel, worthy of the gallows. He has no less absurdly travestied the character of Omar, which he has drawn like that of a cut-throat in a melo-drama.'”

Excerpt: Thomas Jefferson’s Qur’an

Introduction

At a time when most Americans were uninformed, misinformed, or simply afraid of Islam, Thomas Jefferson imagined Muslims as future citizens of his new nation. His engagement with the faith began with the purchase of a Qur’an eleven years before he wrote the Declaration of Independence. Jefferson’s Qur’an survives still in the Library of Congress, serving as a symbol of his and early America’s complex relationship with Islam and its adherents. That relationship remains of signal importance to this day.

That he owned a Qur’an reveals Jefferson’s interest in the Islamic religion, but it does not explain his support for the rights of Muslims. Jefferson first read about Muslim “civil rights” in the work of one of his intellectual heroes: the seventeenth-century English philosopher John Locke. Locke had advocated the toleration of Muslims — and Jews — following in the footsteps of a few others in Europe who had considered the matter for more than a century before him. Jefferson’s ideas about Muslim rights must be understood within this older context, a complex set of transatlantic ideas that would continue to evolve most markedly from the sixteenth through the nineteenth centuries.

Amid the interdenominational Christian violence in Europe, some Christians, beginning in the sixteenth century, chose Muslims as the test case for the demarcation of the theoretical boundaries of their toleration for all believers. Because of these European precedents, Muslims also became a part of American debates about religion and the limits of citizenship. As they set about creating a new government in the United States, the American Founders, Protestants all, frequently referred to the adherents of Islam as they contemplated the proper scope of religious freedom and individual rights among the nation’s present and potential inhabitants. The founding generation debated whether the United States should be exclusively Protestant or a religiously plural polity. And if the latter, whether political equality — the full rights of citizenship, including access to the highest office — should extend to non-Protestants. The mention, then, of Muslims as potential citizens of the United States forced the Protestant majority to imagine the parameters of their new society beyond toleration. It obliged them to interrogate the nature of religious freedom: the issue of a “religious test” in the Constitution, like the ones that would exist at the state level into the nineteenth century; the question of “an establishment of religion,” potentially of Protestant Christianity; and the meaning and extent of a separation of religion from government.

Resistance to the idea of Muslim citizenship was predictable in the eighteenth century. Americans had inherited from Europe almost a millennium of negative distortions of the faith’s theological and political character. Given the dominance and popularity of these anti-Islamic representations, it was startling that a few notable Americans not only refused to exclude Muslims, but even imagined a day when they would be citizens of the United States, with full and equal rights. This surprising, uniquely American egalitarian defense of Muslim rights was the logical extension of European precedents already mentioned. Still, on both sides of the Atlantic, such ideas were marginal at best. How, then, did the idea of the Muslim as a citizen with rights survive despite powerful opposition from the outset? And what is the fate of that ideal in the twenty-first century?

This book provides a new history of the founding era, one that explains how and why Thomas Jefferson and a handful of others adopted and then moved beyond European ideas about the toleration of Muslims. It should be said at the outset that these exceptional men were not motivated by any inherent appreciation for Islam as a religion. Muslims, for most American Protestants, remained beyond the outer limit of those possessing acceptable beliefs, but they nevertheless became emblems of two competing conceptions of the nation’s identity: one essentially preserving the Protestant status quo, and the other fully realizing the pluralism implied in the Revolutionary rhetoric of inalienable anduniversal rights. Thus while some fought to exclude a group whose inclusion they feared would ultimately portend the undoing of the nation’s Protestant character, a pivotal minority, also Protestant, perceiving the ultimate benefit and justice of a religiously plural America, set about defending the rights of future Muslim citizens.

They did so, however, not for the sake of actual Muslims, because none were known at the time to live in America. Instead, Jefferson and others defended Muslim rights for the sake of “imagined Muslims,” the promotion of whose theoretical citizenship would prove the true universality of American rights. Indeed, this defense of imagined Muslims would also create political room to consider the rights of other despised minorities whose numbers in America, though small, were quite real, namely Jews and Catholics. Although it was Muslims who embodied the ideal of inclusion, Jews and Catholics were often linked to them in early American debates, as Jefferson and others fought for the rights of all non-Protestants.

In 1783, the year of the nation’s official independence from Great Britain, George Washington wrote to recent Irish Catholic immigrants in New York City. The American Catholic minority of roughly twenty-five thousand then had few legal protections in any state and, because of their faith, no right to hold political office in New York. Washington insisted that “the bosom of America” was “open to receive … the oppressed and the persecuted of all Nations and Religions; whom we shall welcome to a participation of all our rights and privileges.” He would also write similar missives to Jewish communities, whose total population numbered only about two thousand at this time.

One year later, in 1784, Washington theoretically enfolded Muslims into his private world at Mount Vernon. In a letter to a friend seeking a carpenter and bricklayer to help at his Virginia home, he explained that the workers’ beliefs — or lack thereof — mattered not at all: “If they are good workmen, they may be of Asia, Africa, or Europe. They may be Mahometans [Muslims], Jews or Christian of an[y] Sect, or they may be Atheists.” Clearly, Muslims were part of Washington’s understanding of religious pluralism — at least in theory. But he would not have actually expected any Muslim applicants.

Although we have since learned that there were in fact Muslims resident in eighteenth-century America, this book demonstrates that the Founders and their generational peers never knew it. Thus their Muslim constituency remained an imagined, future one. But the fact that both Washington and Jefferson attached to it such symbolic significance is not accidental. Both men were heir to the same pair of opposing European traditions.

The first, which predominated, depicted Islam as the antithesis of the “true faith” of Protestant Christianity, as well as the source of tyrannical governments abroad. To tolerate Muslims — to accept them as part of a majority Protestant Christian society — was to welcome people who professed a faith most eighteenth-century Europeans and Americans believed false, foreign, and threatening. Catholics would be similarly characterized in American Protestant founding discourse. Indeed, their faith, like Islam, would be deemed a source of tyranny and thus antithetical to American ideas of liberty.

In order to counter such fears, Jefferson and other supporters of non-Protestant citizenship drew upon a second, less popular but crucial stream of European thought, one that posited the toleration of Muslims as well as Jews and Catholics. Those few Europeans, both Catholic and Protestant, who first espoused such ideas in the sixteenth century often died for them. In the seventeenth century, those who advocated universal religious toleration frequently suffered death or imprisonment, banishment or exile, the elites and common folk alike. The ranks of these so-called heretics in Europe included Catholic and Protestant peasants, Protestant scholars of religion and political theory, and fervid Protestant dissenters, such as the first English Baptists — but no people of political power or prominence. Despite not being organized, this minority consistently opposed their coreligionists by defending theoretical Muslims from persecution in Christian-majority states.

As a member of the eighteenth-century Anglican establishment and a prominent political leader in Virginia, Jefferson represented a different sort of proponent for ideas that had long been the hallmark of dissident victims of persecution and exile. Because of his elite status, his own endorsement of Muslim citizenship demanded serious consideration in Virginia — and the new nation. Together with a handful of like-minded American Protestants, he advanced a new, previously unthinkable national blueprint. Thus did ideas long on the fringe of European thought flow into the mainstream of American political discourse at its inception.

Not that these ideas found universal welcome. Even a man of Jefferson’s national reputation would be attacked by his political opponents for his insistence that the rights of all believers should be protected from government interference and persecution. But he drew support from a broad range of constituencies, including Anglicans (or Episcopalians), as well as dissenting Presbyterians and Baptists, who suffered persecution perpetrated by fellow Protestants. No denomination had a unanimously positive view of non-Protestants as full American citizens, yet support for Muslim rights was expressed by some members of each.

What the supporters of Muslim rights were proposing was extraordinary even at a purely theoretical level in the eighteenth century. American citizenship — which had embraced only free, white, male Protestants — was in effect to be abstracted from religion. Race and gender would continue as barriers, but not so faith. Legislation in Virginia would be just the beginning, the First Amendment far from the end of the story; in fact, Jefferson, Washington, and James Madison would work toward this ideal of separation throughout their entire political lives, ultimately leaving it to others to carry on and finish the job. This book documents, for the first time, how Jefferson and others, despite their negative, often incorrect understandings of Islam, pursued that ideal by advocating the rights of Muslims and all non-Protestants.

A decade before George Washington signaled openness to Muslim laborers in 1784 he had listed two slave women from West Africa among his taxable property. “Fatimer” and “Little Fatimer” were a mother and daughter — both indubitably named after the Prophet Muhammad’s daughter Fatima (d. 632). Washington advocated Muslim rights, never realizing that as a slaveholder he was denying Muslims in his own midst any rights at all, including the right to practice their faith. This tragic irony may well have also recurred on the plantations of Jefferson and Madison, although proof of their slaves’ religion remains less than definitive. Nevertheless, having been seized and transported from West Africa, the first American Muslims may have numbered in the tens of thousands, a population certainly greater than the resident Jews and possibly even the Catholics. Although some have speculated that a few former Muslim slaves may have served in the Continental Army, there is little direct evidence any practiced Islam and none that these individuals were known to the Founders. In any case, they had no influence on later political debates about Muslim citizenship.

The insuperable facts of race and slavery rendered invisible the very believers whose freedoms men like Jefferson, Washington, and Madison defended, and whose ancestors had resided in America since the seventeenth century, as long as Protestants had. Indeed, when the Founders imagined future Muslim citizens, they presumably imagined them as white, because by the 1790s “full American citizenship could be claimed by any free, white immigrant, regardless of ethnicity or religious beliefs.”

The two actual Muslims Jefferson would wittingly meet during his lifetime were not black West African slaves but North African ambassadors of Turkish descent. They may have appeared to him to have more melanin than he did, but he never commented on their complexions or race. (Other observers either failed to mention it or simply affirmed that the ambassador in question was not black.) But then Jefferson was interested in neither diplomat for reasons of religion or race; he engaged them because of their political power. (They were, of course, also free.)

But even earlier in his political life — as an ambassador, secretary of state, and vice president — Jefferson had never perceived a predominantly religious dimension to the conflict with North African Muslim powers, whose pirates threatened American shipping in the Mediterranean and eastern Atlantic. As this book demonstrates, Jefferson as president would insist to the rulers of Tripoli and Tunis that his nation harbored no anti-Islamic bias, even going so far as to express the extraordinary claim of believing in the same God as those men.

The equality of believers that Jefferson sought at home was the same one he professed abroad, in both contexts attempting to divorce religion from politics, or so it seemed. In fact, Jefferson’s limited but unique appreciation for Islam appears as a minor but active element in his presidential foreign policy with North Africa — and his most personal Deist and Unitarian beliefs. The two were quite possibly entwined, with their source Jefferson’s unsophisticated yet effective understanding of the Qur’an he owned.

Still, as a man of his time, Jefferson was not immune to negative feelings about Islam. He would even use some of the most popular anti-Islamic images inherited from Europe to drive his early political arguments about the separation of religion from government in Virginia. Yet ultimately Jefferson and others not as well known were still able to divorce the idea of Muslim citizenship from their dislike of Islam, as they forged an “imagined political community,” inclusive beyond all precedent.

The clash between principle and prejudice that Jefferson himself overcame in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries remains a test for the nation in the twenty-first. Since the late nineteenth century, the United States has in fact become home to a diverse and dynamic American Muslim citizenry, but this population has never been fully welcomed. Whereas in Jefferson’s time organized prejudice against Muslims was exercised against an exclusively foreign and imaginary nonresident population, today political attacks target real, resident American Muslim citizens. Particularly in the wake of Sept. 11 and the so-called War on Terror, a public discourse of anti-Muslim bigotry has arisen to justify depriving American Muslim citizens of the full and equal exercise of their civil rights.

For example, recent anti-Islamic slurs used to deny the legitimacy of a presidential candidacy contained eerie echoes of founding precedents. The legal possibility of a Muslim president was first discussed with vitriol during debates involving America’s Founders. Thomas Jefferson would be the first in the history of American politics to suffer the false charge of being a Muslim, an accusation considered the ultimate Protestant slur in the eighteenth century. That a presidential candidate in the twenty-first century should have been subject to much the same false attack, still presumed as politically damning to any real American Muslim candidate’s potential for elected office, demonstrates the importance of examining how the multiple images of Islam and Muslims first entered American consciousness and how the rights of Muslims first came to be accepted as national ideals. Ultimately, the status of Muslim citizenship in America today cannot be properly appreciated without establishing the historical context of its eighteenth-century origins.

Muslim American rights became a theoretical reality early on, but as a practical one they have been much slower to evolve. In fact, they are being tested daily. Recently, John Esposito, a distinguished historian of Islam in contemporary America, observed, “Muslims are led to wonder: What are the limits of this Western pluralism?” Thomas Jefferson’s Qur’an documents the origins of such pluralism in the United States in order to illuminate where, when, and how Muslims were first included in American ideals.

Until now, most historians have proposed that Muslims represented nothing more than the incarnated antithesis of American values. These same voices also insist that Protestant Americans always and uniformly defined both the religion of Islam and its practitioners as inherently un-American. Indeed, most historians posit that the emergence of the United States as an ideological and political phenomenon occurred in opposition to eighteenth-century concepts about Islam as a false religion and source of despotic government. There is certainly evidence for these assumptions in early American religious polemic, domestic politics, foreign policy, and literary sources. There are, however, also considerable observations about Islam and Muslims that cast both in a more affirmative light, including key references to Muslims as future American citizens in important founding debates about rights. These sources show that American Protestants did not monolithically view Islam as “a thoroughly foreign religion.”

This book documents the counterassertion that Muslims, far from being definitively un-American, were deeply embedded in the concept of citizenship in the United States since the country’s inception, even if these inclusive ideas were not then accepted by the majority of Americans. While focusing on Jefferson’s views of Islam, Muslims, and the Islamic world, it also analyzes the perspectives of John Adams and James Madison. Nor is it limited to these key Founders. The cast of those who took part in the contest concerning the rights of Muslims, imagined and real, is not confined to famous political elites but includes Presbyterian and Baptist protestors against Virginia’s religious establishment; the Anglican lawyers James Iredell and Samuel Johnston in North Carolina, who argued for the rights of Muslims in their state’s constitutional ratifying convention; and John Leland, an evangelical Baptist preacher and ally of Jefferson and Madison in Virginia, who agitated in Connecticut and Massachusetts in support of Muslim equality, the Constitution, the First Amendment, and the end of established religion at the state level.

The lives of two American Muslim slaves of West African origin, Ibrahima Abd al-Rahman and Omar ibn Said, also intersect this narrative. Both were literate in Arabic, the latter writing his autobiography in that language. They remind us of the presence of tens of thousands of Muslim slaves who had no rights, no voice, and no hope of American citizenship in the midst of these early discussions about religious and political equality for future, free practitioners of Islam.

Imagined Muslims, along with real Jews and Catholics, were the consummate outsiders in much of America’s political discourse at the founding. Jews and Catholics would struggle into the twentieth century to gain in practice the equal rights assured them in theory, although even this process would not entirely eradicate prejudice against either group. Nevertheless, from among the original triad of religious outsiders in the United States, only Muslims remain the objects of a substantial civic discourse of derision and marginalization, still being perceived in many quarters as not fully American. This book writes Muslims back into our founding narrative in the hope of clarifying the importance of critical historical precedents at a time when the idea of the Muslim as citizen is, once more, hotly contested.

Excerpted from Thomas Jefferson’s Qur’an by Denise A. Spellberg. Copyright 2013 by Denise A. Spellberg.

The political aspects of Islam

The first mention of the Shura in the Qur’an comes in the 2nd Sura of Qur’an 2:233 in the matter of the collective family decision regarding weaning the child from mother’s milk. This verse encourages that both parents decide by their mutual consultation about weaning their child.

The 42nd Sura of Qur’an is named as Shura. The 38th verse of that Sura suggests that shura is praiseworthy life style of a successful believer. It also suggests that people whose matter is being decided be consulted. It says: “Those who hearken to their Lord, and establish regular Prayer; who (conduct) their affairs by mutual consultation among themselves; who spend out of what We bestow on them for Sustenance” [are praised] The 159th verse of 3rd Sura orders Muhammad to consult with believers. The verse makes a direct reference to those (Muslims) who disobeyed Muhammad, indicating that ordinary, fallible Muslims should be consulted. It says: Thus it is due to mercy from God that you deal with them gently, and had you been rough, hard hearted, they would certainly have dispersed from around you; pardon them therefore and ask pardon for them, and take counsel with them in the affair; so when you have decided, then place your trust in God; surely God loves those who trust.

The first verse only deals with family matters. The second proposed a lifestyle of people who will enter heavens and is considered the most comprehensive verse on shura. The third verse advices on how mercy, forgiveness and mutual consultation can win over people.

Muhammad made all his decisions in consultation with his followers unless it was a matter in which God has ordained something. It was common among Muhammad’s companions to ask him if a certain advice was from God or from him. If it was from Muhammad, they felt free to give their opinion. Some times Muhammad changed his opinion on the advice of his followers like his decision to defend the city of Madinah by going out of the city in Uhad instead of from within the city.

Arguments over shura began with the debate over the ruler in the Islamic world. When Muhammad died in 632 CE, a tumultuous meeting at Saqifah selected Abu Bakr as his successor. This meeting did not include some of those with a strong interest in the matter—especially Ali ibn Abi Talib, Muhammad’s cousin and son-in-law; people who wanted Ali to be the caliph (ruler) became known as Shia ul-Ali (party of Ali) still consider Abu Bakr an illegitimate leader of the caliphate.